Some Psychological Problems Resulting from the Practice of History

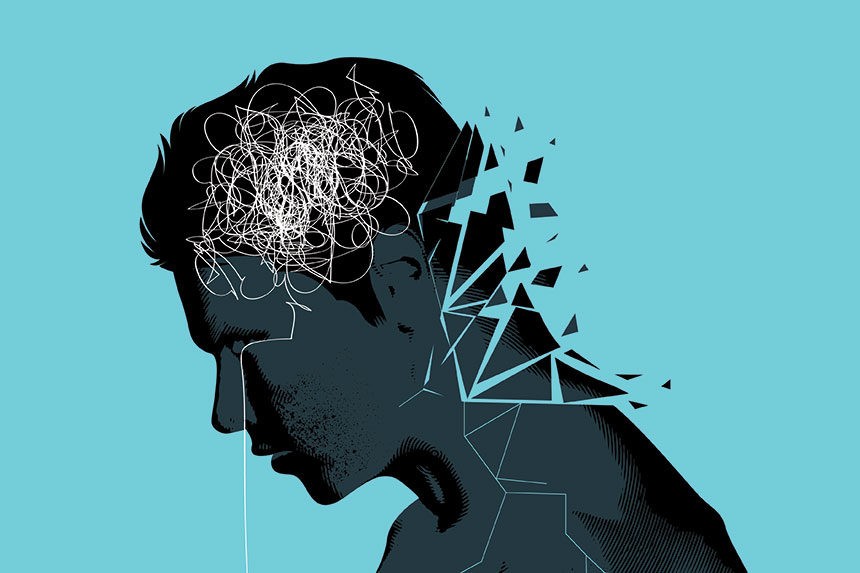

So let my fellow historians excuse me for raising this question: Does specialization in history and engagement with it have psychological effects on those who practice it? The answer—most certainly—is yes. Yet few people, even among historians themselves, ever pay attention to this point. A historian is not merely a transmitter of past human experience. His constant engagement with the past—sometimes to the point of immersion—can lead him to detach from the present, leaving him in a perpetual tension between two contrasting temporalities: the past with all its details, events, and otherness, and the present with all its burdens and challenges.

It is well known in psychology that continual dwelling on the past leads to numerous psychological problems, chief among them depression. How much more so, then, for those who live in a past that is entirely different. The historian experiences a condition of alienation from the present, in every sense of that phrase: the time is different, the culture is different, the language is different, and often the religion is different as well. At times, a historian may even look upon the era he studies with greater reverence and admiration than he accords to his own era—what we may call excessive nostalgia—which leaves him feeling isolated from society and emotionally detached from the “spirit of the age.” Such saturation in the past deprives the historian of the ability to fully engage with the present or to envision the future.

Conversely, when historians study tragic past events—massacres, famines, genocides—they may suffer psychologically, especially when they empathically inhabit the perspective of victims, drowning in sorrow and melancholy. This produces a form of secondary trauma, similar to what therapists experience when listening to their patients’ painful stories. Moreover, when a historian delves deeply into big questions, the collapse of civilizations, the outbreak of wars, or the spread of plagues, he may come to feel the fragility of both humanity and time itself, which can give rise to what we might term existential anxiety.

Among the most significant negative effects of historical study is death anxiety, particularly for those who specialize in phenomena of mortality and human finitude. And in his attempt to strike a balance between scientific objectivity and personal opinion—and in his constant struggle over whether to transmit the past exactly as it was or to interpret it through the lens of his own era—the historian experiences a kind of cognitive dissonance that only the professional historian can truly recognize.